By Miriam Edlich-Muth

Recently I attended the ‘Parchment, Paper and Pixels’ conference in Maastricht. Set under the glorious arches of the former Franciscan monastery that houses the Regional Historical Centre of Limburg the topics of the conference skirted both the material and the ephemeral. Several papers addressed the digital strategies by which the gap between the two is being bridged in the growing numbers of online manuscript collections, which deploy the metaphor of the library to offer two-dimensional representations of these literary objects from the past.

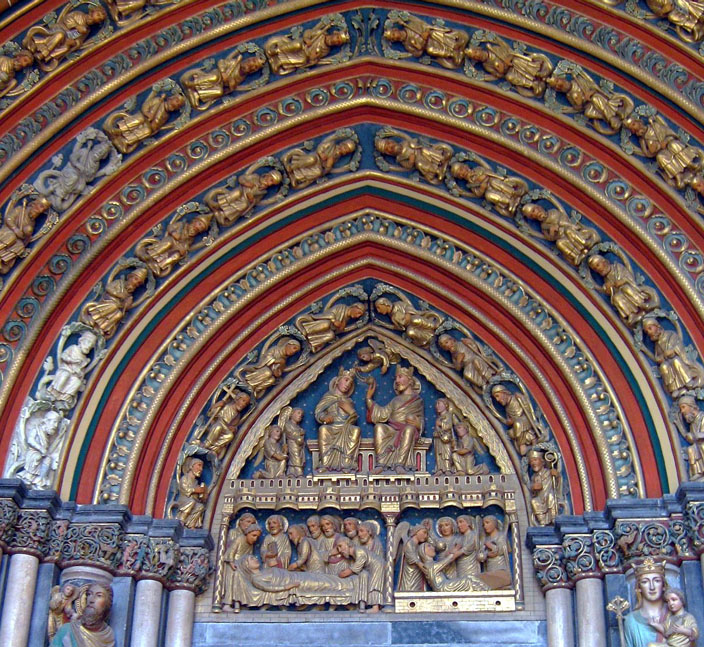

The excursion to the Basilica of St Servatius on the first day, brought to mind the continuing tensions that arise out of the interplay between the material objects of the past and the intangible meaning with which they become associated. Visitors entering the church through the south portal are immediately confronted with that dichotomy on hearing that one of the eight almost life-sized statues decorating the arch above the entrance underwent an unintentional shift from man to woman in the nineteenth century. Thus the restoration process refigured the less well-known form of Simeon carrying the young Christ into a more familiar representation of Mary and the Christ child. The implication is that the churchgoers of the time had come to overlook the less ubiquitous story of Simeon to the extent that they were no longer able to recognise the figure that the statue was supposed to represent, neatly illustrating the fact that the memorial function of the visual arts can only be fulfilled within a network of storytelling that is shared across the centuries. In this case it appears that even the monumental continuity of Christian culture in the centuries preceding the nineteenth century was not sufficient to allow the story of Simeon and the young Christ to continue to assert itself over the more immediate association of the Christ child statue with the Madonna.

That the narratives incorporated into the architecture of churches such as this one have been partly obscured by the passing of time constitutes no small part of the fascination these buildings inspire. With a recently rediscovered second crypt and flagstones that can be lifted to show the illuminated graves of former churchmen, the Basilica of Saint Servatius does not disappoint in terms of architectural hermeneutics. However, what is perhaps more interesting is that even where no biblical stories have been referenced, the very architectural structure of the church has invited the local community to weave narratives around its history. This becomes most apparent at the top of the church tower, which contains a good-sized room, whose many windows, delicately mosaicked floor and perfectly balanced proportions suggest a stately reception room rather than an attic. The original purpose of this room, now known as the Emperor’s Hall, is no longer known. All the more reason, then, for local tradition to claim that this room was intended as a lodging for Charlemagne himself on his visits to Maastricht. Leaving aside the question of whether medieval royalty was often housed in isolated tower-top rooms, contemporary visitors can observe that the room has been imprinted with new narratives over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as the names engraved into the soft stone over that period bear witness to the lovers and school children who have visited the place.

However, the written traces of modern visitors pale in comparison to the deep tracks that the feet of innumerable pilgrims have left in the stone floor of the crypt that housed Saint Servatius’ relics. Accordingly, one of the more striking stories associated with the building concerns Saint Servatius himself – not the living man, but the dead body – whose status as a valuable relic served as a focal point for escalating tensions between the people of Maastricht and the Saxons in the later Middle Ages. The story, the bare bones of which are deeply familiar, tells of a Saxon dignitary, who had the relics of Saint Servatius taken away to be housed by a new chapter he was founding. The people of Maastricht were unhappy about this loss of their most important relics, so when they were invited to a feast at the new chapter they reportedly refused their drink and once their hosts were drunk they attacked them, stole the relics back and returned them to Maastricht where they have remained ever since. Clearly, like the rooms and statues incorporated into the architecture of the church, the relics of Saint Servatius have continued to generate new narratives and agglomerate new meaning long after Servatius’ death, allowing them to become associated not just with heavenly salvation, but with worldly territorial conflicts, in which the totemic value of the relics played a part in shoring up the regional identity of Maastricht.

Get Social