As soon as I heard the news of the toppling of the slaver Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol, I was reminded irresistibly of Richard III. Just as Colston’s statue was pulled down, rolled roughly through the streets, and thrown into the harbour by a jubilant crowd, so Richard’s remains were said to have been treated in 1538, when the priory he was buried in was dissolved. According to the historian John Speed, Richard’s tomb was “pulled down and utterly defaced,” and his corpse carried through Leicester to be thrown into the River Soar. In the Victorian era, a plaque was mounted by Bow Bridge to mark the site where Richard’s body had supposedly been submerged.

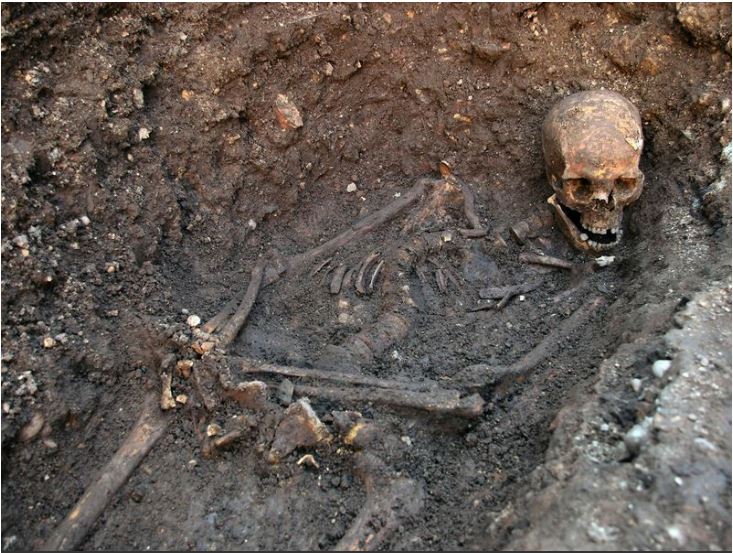

The discovery of Richard III’s skeleton in Leicester in 2012 proved that he had not, after all, suffered Colston’s fate. Yet still their two bodies – one of metal, one of bone – seem to mirror each other uncannily. David Olusoga has written vividly of the spectacle of Colston’s statue, lying in a Bristol lock-up. “His fall to earth, and his rough journey across the asphalt to Bristol harbour, into which he was thrown, have left their marks. Colston is now covered in scrapes and scratches. There’s a hole in his left buttock and his walking stick is missing.” The present condition of Colston’s statue recalls the punishment inflicted on Richard’s body, as revealed by osteological analysis. In addition to shattering blows to the cranium, which caused his death, the skeleton bore evidence of a post-mortem wound in the right buttock, marking the pelvic bone. The body of the king, as it was left naked on display in Leicester for several days before his burial, must have formed a spectacle in some ways similar to Colston’s.

All of this may seem like a handful of insignificant coincidences. The most important connection between Colston and Richard III, it is fair to say, is that both were outstandingly wicked men. Neither deserves to be celebrated today, or commemorated by any form of public monument. Our attention is better directed to the histories of the men, women, and children who suffered under their despotism; and, in Colston’s case, to the brave protesters who put an end to his monument’s insulting reign in Bristol. And yet, paradoxically perhaps, one way to recover and begin to honour these histories is by looking anew at what remains of Colston’s statue and the body of Richard III. As Olusoga observes, “Beaten-up, bloodied and graffitied, Colston’s statue is no longer just another piece of mediocre, late-Victorian public art… [T]he graffiti Colston has acquired is as historically significant as the object on to which it was scrawled.” Richard III’s body and Colston’s statue have become bearers of complex histories.

Setting the spectacle of Richard’s skeleton alongside Colston’s battered monument can help illumine what makes each of them so visually arresting, and so historically instructive. In either case, to look upon their scars and wounds brings us into almost palpable contact with a specific moment in the past, when those blows were delivered and received. These after-images of sudden violence forge a constellation between distinct historical moments; in this sense, they make the past present. At the same time, weathering by the elements of earth, water, and air compels them to bear witness to the gulf that separates then and now. Like our own bodies, Richard’s body and Colston’s statue were not fated to last. The multiple histories we glimpse in gazing on their broken forms are mediated through our own experience of embodiment.

Those who decry the toppling of monuments like Colston’s, or those of Confederate leaders in the United States, tell us that statues such as these embody the nation’s history. They charge the activists who seek to bring them down with trying to deny or forget the past. In the flowery prose of President Trump’s recent executive order, “These statues are silent teachers in solid form of stone and metal. They preserve the memory of our American story.” Yet statues and monuments are notoriously poor teachers of history, if by this we mean an understanding of the past as it was, not to mention historical process. Their most profound message is often anti-historical, or at least ahistorical. Through their silent persistence from one generation and one century to the next, they imply that society’s values are essentially timeless, that the most important things do not and should not change.

Colston’s statue only became capable of embodying history when it was treated as a body – a body that could be felled, battered, and scarred, a body like Richard III’s. The violence of its toppling has made buckled metal speak, as Richard’s pierced bones still speak. Through the freshly opened gap in its buttock we can glimpse multiple pasts: the struggles and survival of the enslaved men and women who laboured on Colston’s plantations in the seventeenth century; the inhuman bargain that bore fruit in Bristol’s eighteenth-century civic flowering; the narrow values of the late-Victorian elite who paid for the statue’s erection; the sunlit day in June of this year when it finally plummeted from its plinth.

This is not to say that iconoclastic violence is the only means whereby our “silent teachers” can be made to bear witness to history. But it does suggest that if we want statues and monuments to tell us something meaningful about the past, we should begin by understanding them not as symbols but as bodies – that is, as inescapably physical entities, with personal histories and material biographies, partaking of both the body’s grandeur and its mortality. Seen in this light, every old statue, whether standing or toppled, has a story to tell, not one of timeless values but of historical change, contingency, and struggle.

Get Social