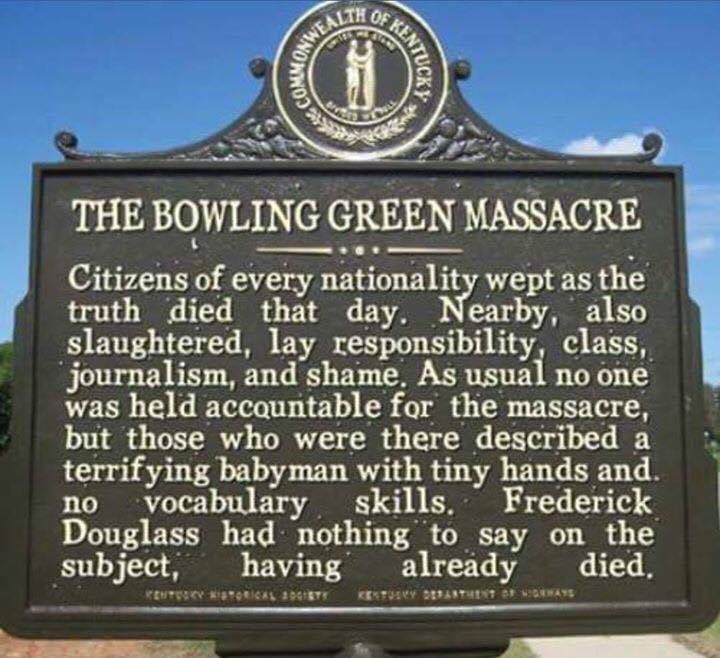

Do you remember the Bowling Green Massacre?

This mysterious atrocity was introduced to the world by Presidential Counselor Kellyanne Conway in an interview on Thursday 2 February. Justifying Trump’s immigration ban, Conway reminded us that “two Iraqis came here to this country, were radicalized, and were the masterminds behind the Bowling Green Massacre. Most people don’t know that because it didn’t get covered.”

As many news agencies quickly pointed out, the Bowling Green Massacre didn’t get covered because it never happened. In fact, two Iraqi citizens living in Bowling Green, Kentucky, were sentenced in 2013 for attempting to send money and weapons to al-Qaeda in Iraq. They were indeed guilty of a crime, but not of planning or committing acts of violence on US soil.

Twitter has responded with predictable delight to the fictitious #BowlingGreenMassacre. There have been mock vigils, satirical memorials, and promises never to forget what no one can, in fact, remember. “Where were you the day it didn’t happen?” A commemorative website set up to honour the victims of the massacre leads to a donation page for the American Civil Liberties Union. Many of the responses gesture to a wider critique of the way terrorist massacres are commemorated and exploited for political gain.

In a curious way, the case of the Bowling Green Massacre proves the point of the DEEPDEAD project. Power today, as in the past, acts in the name of the dead. The problem for Trump is that there are no actual dead people available to back his ban on the admission of refugees and immigrants from seven predominantly Muslim countries. In the last 35 years, not a single person has been killed in a terrorist attack on US soil carried out either by a refugee or by a national of Iraq, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Syria, Sudan, or Yemen. Not a single useful death.

When the dead do not exist, they must be invented. Thus Conway reminds the nation of the terrible massacre that pretty much could have happened in Kentucky. “Alternative facts” like the Bowling Green Massacre are easy enough to disprove. But the problem runs deeper. On a rhetorical level, Trump and his administration appear to be deeply invested in the claim that they act on behalf of dead victims, who must be honoured and avenged. Disused factories are likened to “tombstones.” The President throws around the word “carnage,” often without a clear referent, to justify a range of actions. Such language strikes a powerful, time-honoured chord. Trump may be no poet, but he understands how to elicit responses honed by centuries of commemorative poetry.

There is a long tradition of the poetry of massacre, wherein the poet recounts the details of an atrocity in order to demand some action or sacrifice on behalf of the dead. John Gower’s Vox Clamantis, in response to the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, provides an example from medieval England. But the poem that’s been on my mind since Conway spoke on Thursday is John Milton’s “On the Late Massacre in Piedmont”:

Avenge, O Lord, thy slaughtered saints, whose bones

Lie scattered on the Alpine mountains cold,

Even them who kept thy truth so pure of old,

When all our fathers worshipped stocks and stones;

Forget not: in thy book record their groans

Who were thy sheep and in their ancient fold

Slain by the bloody Piemontese that rolled

Mother with infant down the rocks. Their moans

The vales redoubled to the hills, and they

To Heaven. Their martyred blood and ashes sow

O’er all the Italian fields where still doth sway

The triple tyrant; that from these may grow

A hundred-fold, who having learnt thy way

Early may fly the Babylonian woe.

The poem records the (unfortunately real) massacre of Waldensian communities in Piedmont by the forces of the Duke of Savoy in 1655. Milton saw the Waldensians as having practiced a form of pure Christianity, untainted by Catholic superstition and comparable to Protestantism. They had kept true to the original Christian faith while Milton’s own English ancestors had been superstitiously worshipping “stocks and stones” (that is, venerating images in the era of Catholicism).

A couple of things strike me about the sonnet. Milton propounds a familiar opposition between the “pure” religion of the Waldensians/Protestants and a corrupt Catholicism which is obsessed with material objects and images. Yet this opposition is troubled by the poem’s fascination with the material remains of the martyrs. The rhyme scheme of the first quatrain sets up an association between the pitiable “bones” of the Waldensians and the “stones” venerated by Catholic idol-worshippers; if these objects are opposed to one another, they are also in some way comparable. Later in the sonnet, Milton effectively weaponizes human remains in the form of “martyred blood and ashes” to be sprinkled over Italy. This ostensibly anti-Catholic poem veers repeatedly toward the language of relic-worship. Is the irony unintentional, or self-conscious? Is Milton perhaps acknowledging that human remains will always play a central role in religion – the only difference being whether they are seen as relics invested with a power of their own, or as instruments of divine action?

The second point of interest – more pertinent to today’s debates – is that Milton does not call for a reciprocal massacre. Indeed, though it begins with the imperative “Avenge,” the sonnet does not promote violence of any kind. Rather, Milton calls on God to “sow” the blood and ashes of the Waldensians like seeds over Italy. From these seeds will spring a generation wise enough to reject Roman Catholicism. In other words, God’s vengeance will consist in allowing the physical remains of the martyrs – and the pity or horror they inspire – to serve as a source of education and enlightenment.

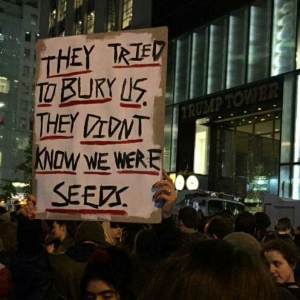

Echoes of Milton’s sonnet can be heard today, but not, I think, in the invocation of atrocities like the fictional massacre of Bowling Green to justify punitive policies. Rather, I hear echoes of Milton in the slogan I’ve seen at several recent protests:

“They tried to bury us. They didn’t know we were seeds.”

Get Social